High-Availability Seamless Redundancy, or HSR, is one of the most important communication technologies for digital substations and industrial systems that must operate continuously without interruption. It is designed for networks where data must always be delivered, even when a failure occurs. Protection relays, merging units, and automation devices depend on communication that never drops a packet, because even a single missed message can cause incorrect operation. HSR makes this possible by ensuring that every frame is always sent along two paths, guaranteeing availability even if one path is lost.

High-Availability Seamless Redundancy belongs to the family of zero-time recovery redundancy methods. Unlike traditional redundancy protocols that need time to detect failures and rebuild the network, HSR works with no switchover delay. Communication continues instantly because alternative paths are already active. This makes it particularly suitable for IEC 61850 environments where Sampled Values and GOOSE messages must be delivered with strict timing requirements.

Contenu de l'Article

HSR Architecture and Operating Principle

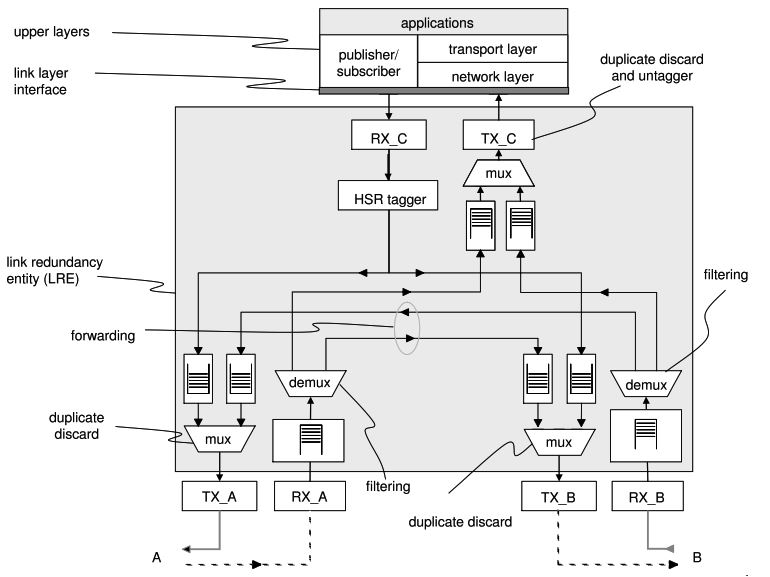

An HSR network is built around a ring of interconnected devices. Each device has two Ethernet ports and participates directly in forwarding the traffic. These devices are known as doubly attached nodes (DNAH). When a device sends a frame, it issues two identical copies simultaneously, one through each port. The two copies travel in opposite directions around the ring. Every other device receives both copies and uses the first one that arrives. When the second copy appears, it is immediately discarded.

This approach ensures that communication always has a second path available. If one link in the ring is broken, the frame still arrives from the other side. There is no interruption in communication because the network does not need to detect the failure or change topology. Communication continues with the remaining available direction. The devices themselves are responsible for duplicating frames, detecting duplicates, and forwarding traffic around the ring.

Because the forwarding happens at each device, they must contain an internal forwarding engine. This engine passes frames from one port to the other after checking whether the frame has been seen before. Forwarding is fast and predictable. Each device adds only a small amount of latency, usually a few microseconds. Even when many nodes are used, the total delay remains manageable if the ring is properly designed.

HSR Frame Handling and Duplicate Detection

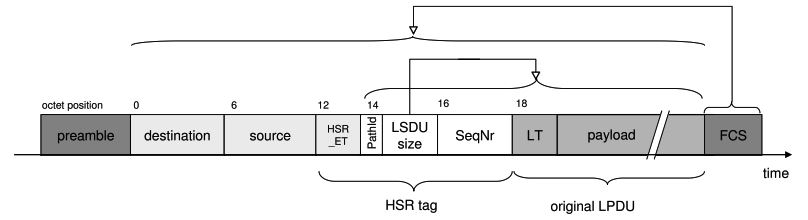

HSR introduces a special HSR tag that is inserted into every frame before it is transmitted. This HSR tag includes a sequence number and identification information that help nodes determine if a frame is new or duplicated. When a node receives a frame, it first checks the header. If the sequence number and source match an entry it has already processed recently, the frame is discarded. If not, the node forwards the frame to its other port and processes it if necessary.

Duplicate detection ensures that the network does not suffer from looping traffic. Without this mechanism, frames would circulate endlessly around the ring. The network would quickly saturate and fail. HSR’s built-in duplicate suppression prevents this and keeps the communication efficient.

HSR also uses special control frames to maintain awareness of which devices are active and reachable. These supervision frames allow each node to build a table of other devices, including information about which port they are reachable through. This helps monitor the health of the ring and detect whether certain paths are missing.

Integrating Non-HSR Devices Using RedBoxes

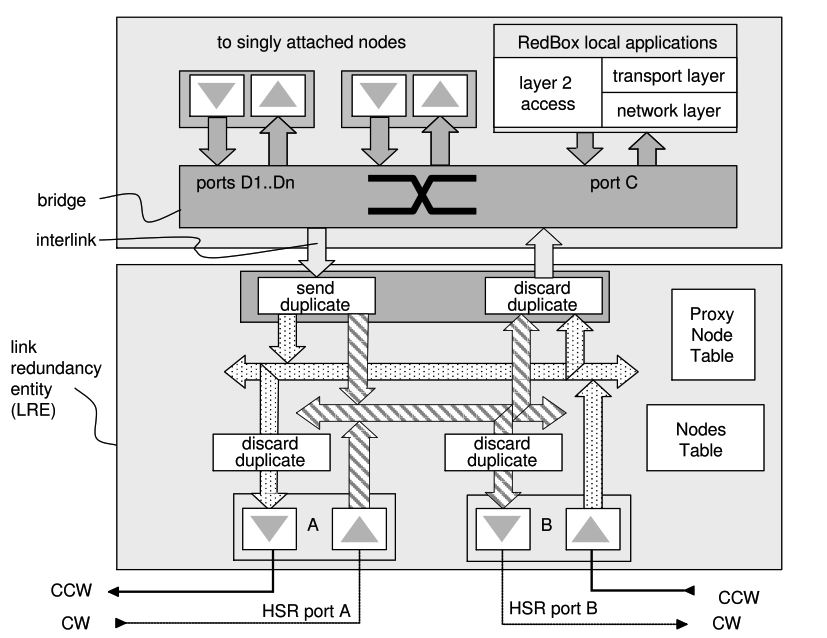

Not every device in a substation supports HSR natively. Legacy devices or servers often have only a single Ethernet interface and cannot duplicate frames or process the HSR header. To integrate such devices into an HSR ring, a special component known as a RedBox is used.

A RedBox behaves as an HSR node toward the ring while offering standard Ethernet connectivity to external devices. It represents these external devices inside the ring. When a non-HSR device sends a frame to the RedBox, the RedBox inserts the proper HSR header, duplicates the frame, sends it into the ring, and filters duplicates on behalf of that device. It also sends supervision information so that all nodes recognize the non-HSR device as part of the network.

Using RedBoxes, HMI stations, SCADA servers, test equipment, or engineering laptops can participate safely in an HSR network without requiring any modification.

Connecting Multiple Rings with QuadBoxes

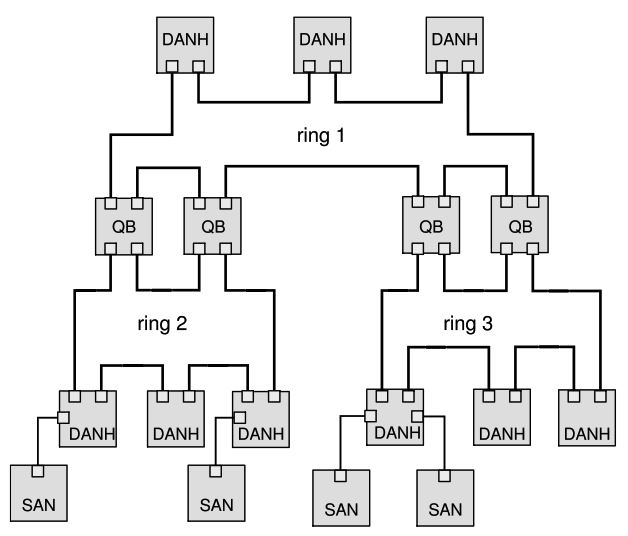

Some substations require more than one HSR ring. For example, one ring may carry process-level traffic for a bay, while another ring supports a different bay or protection zone. Interconnecting these rings requires a QuadBox.

A QuadBox contains multiple HSR interfaces and ensures frames are forwarded correctly between rings. It performs duplicate suppression on each ring independently and prevents loops from forming between rings. When designed correctly, multiple rings can operate together while keeping traffic local to each ring as much as possible.

QuadBoxes support more advanced topologies, such as two rings connected through a central point or expanded HSR networks with several interconnected loops. The forwarding behavior is carefully controlled so that redundancy remains seamless across all segments.

Traffic Characteristics and Performance Considerations

HSR duplicates every frame, so traffic load must be considered carefully. When Sampled Values are used at high sampling rates, the amount of traffic doubles because each frame is sent in both directions. Additionally, every device forwards every frame it receives, adding to the cumulative load on the ring.

This means that HSR rings must not be designed with excessive numbers of nodes. The total traffic, combined with forwarding delays at each node, can increase latency if the ring grows too large. Smaller rings, sometimes dedicated to individual bays, are often preferred for process bus applications.

The forwarding delay inside each device is deterministic. This means that the overall latency of the ring can be calculated in advance. This predictability is one of the reasons HSR is suitable for real-time communication. However, network engineers must consider worst-case scenarios, including high traffic and multiple simultaneous Sampled Value streams.

GOOSE and Sampled Values over High-Availability Seamless Redundancy

HSR is well suited for GOOSE messaging. Because GOOSE frames are multicast and retransmitted periodically, receiving two copies provides even more robustness. The low forwarding delay around the ring ensures that GOOSE communication remains fast enough for high-speed protection schemes. Even if a link fails, the frame reaches its destination immediately through the other direction.

Sampled Values benefit strongly from HSR because they require uninterrupted, continuous streams. A break in Sampled Values can cause relays to lose synchronization, misinterpret measurements, or trigger protection alarms. HSR ensures that these streams continue without interruption, even when the physical network experiences a fault.

However, engineers must design the ring so that Sampled Values do not exceed bandwidth limits. Large numbers of merging units must be distributed across multiple rings or use hybrid architectures combining HSR and other redundancy methods.

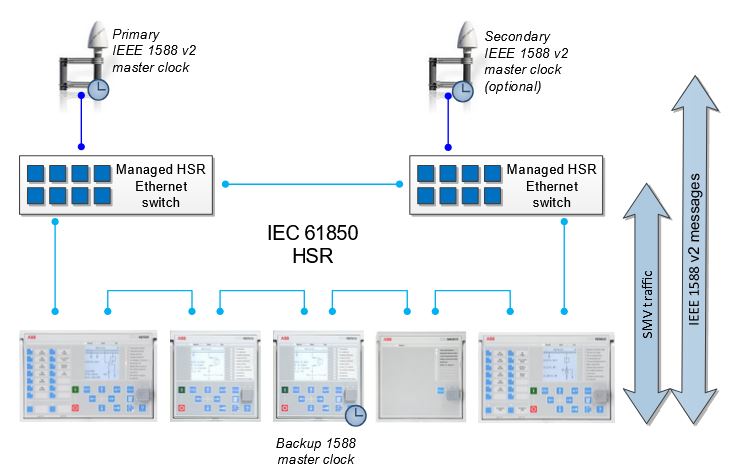

Time Synchronization in HSR Networks

Time synchronization using IEEE 1588 can operate within an HSR network. Timing packets are forwarded around the ring like any other frame. Because they also arrive in two directions, the timing algorithm must be implemented carefully so that it uses the correct packet and avoids confusion from duplicates.

Devices performing timing must be aware of forwarding delays introduced by each node. These delays must be accounted for so that the time remains accurate. This can be done through mechanisms such as Transparent Clock or Boundary Clock behavior, depending on the network design.

PTP traffic should always receive the highest priority, ensuring that timing frames move through the ring with minimal variation. Stable timing is essential for Sampled Values, especially in substations using high sampling rates or synchrophasor measurement.

Failure Handling and Zero-Time Recovery

The main strength of HSR is its behavior during failures. When a link between two nodes breaks, frames sent in that direction simply stop traveling. The frames sent in the opposite direction continue around the ring and reach their destination. Devices do not need to change configuration or perform recovery steps. Communication continues immediately because both paths are always active.

If a node fails, the ring becomes open at that point. The remaining path still supports all communication. If two failures occur at adjacent points, the ring may become segmented. This situation can be mitigated by careful design or by using multiple interconnected rings. Even in rare cases of segmentation, properly designed HSR networks can maintain local communication until the fault is corrected.

This zero-time recovery behavior is essential for digital substations. Protection and control equipment cannot tolerate even short interruptions. With HSR, the worst case is a slight change in delay depending on which path delivers the frame first, but no frames are lost and no reconvergence occurs.

Designing Reliable HSR Architectures

Building a reliable HSR system requires careful planning. The number of nodes in a ring must remain within reasonable limits to avoid excessive cumulative delay. Process bus applications often use separate rings for each bay rather than a single large ring. Supervisory or station bus traffic may share a ring with fewer delays.

Non-HSR devices should be integrated using RedBoxes, and their number should be limited. Each RedBox represents a translation point where traffic enters the ring, and too many connections can overload the forwarding flow.

Redundant physical paths must be planned with symmetry in mind. Unequal cable lengths can introduce delay differences, affecting time-sensitive applications. Fiber cabling is generally preferred, with balanced lengths between bidirectional paths.

Monitoring of supervision information is also important. Nodes maintain tables of neighbors and detected paths. These tables help identify broken links or failed devices and allow maintenance teams to react quickly.

Combining High-Availability Seamless Redundancy with other redundancy technologies is common in substations. For example, the process bus might use HSR rings for merging units, while the station bus uses PRP for SCADA and gateway communication. RedBoxes can bridge these two redundancy domains, ensuring compatibility without compromising performance.

Understanding HSR Frame Flow in the Ring

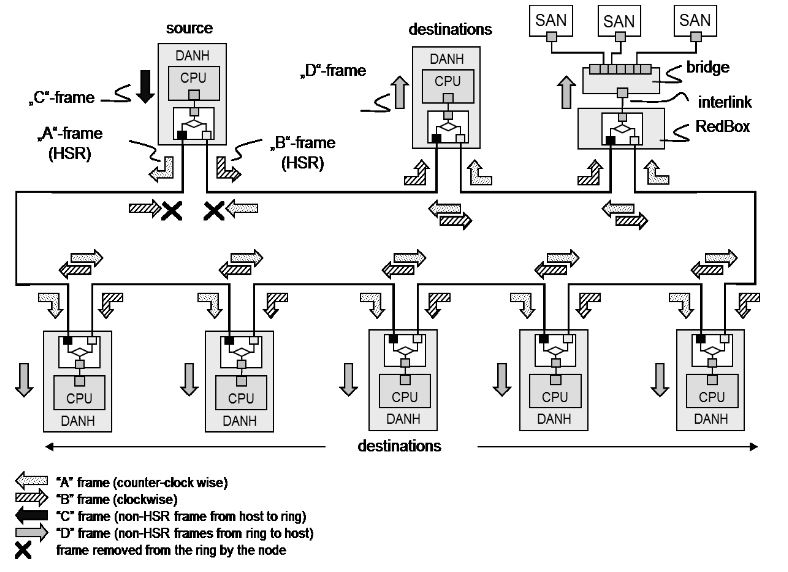

The diagram illustrates how frames circulate inside an HSR ring and how each device handles the traffic depending on its role. Every HSR node has two ports and an internal forwarding engine. When a device generates a frame, it sends two copies into the ring: one traveling clockwise and the other counter-clockwise. These are often called the A-frame and B-frame. Both copies move independently through the ring, and every device that receives them makes a decision based on whether the frame is new or already processed.

A device that sits inside the HSR ring receives each frame twice, once from each direction. It forwards the first copy it sees to the opposite port and passes it to its internal application if the frame is addressed to it. When the second copy arrives, the node recognizes it by its sequence number and discards it. This ensures that no node processes the same information twice and prevents the ring from filling with unnecessary traffic. The process continues as the frames propagate through the entire ring until every destination device has received the first valid copy.

The diagram also shows what happens when a link fails. If the ring is broken at one point, the frames traveling in that direction simply stop at the break. The second copy, moving in the opposite direction, still reaches all nodes without interruption. No switching time is required, and no detection or recalculation takes place. The ring keeps operating normally, using the surviving path to deliver frames.

In mixed networks, not all devices are native HSR nodes. Some equipment still uses standard Ethernet and cannot attach directly to the ring. These devices connect through a RedBox. The RedBox plays the role of an HSR node on one side and a normal Ethernet interface on the other. It inserts and removes HSR tags, duplicates outgoing frames, filters redundant incoming frames, and ensures that external devices appear as fully functional participants in the redundant network. In the diagram, the RedBox receives ordinary frames from the non-HSR devices, injects them into the ring as HSR traffic, and forwards them in both directions.

The C-frame and D-frame indicators in the diagram represent the translation steps inside the RedBox. When a non-HSR device sends a frame toward the ring, the RedBox wraps it with an HSR header and sends it as two copies into both directions of the ring. When an HSR frame is destined for a non-HSR device, the RedBox removes the HSR header, suppresses duplicates, and forwards only a single frame to the external device.

The arrows flowing downward in each box represent traffic that reaches its endpoint and is consumed by the device. The arrows flowing sideways show how each frame continues around the ring until it completes a full loop. When a frame completes the loop and returns to its source, that source removes it from the ring. Without this cleanup step, frames would circulate indefinitely. Each device therefore checks whether a frame has arrived from both directions. Once the source sees that the frame has returned, it knows that every other node in the ring has already received it and it can safely remove the remaining copy.

Overall, this diagram demonstrates the core behavior of HSR: dual transmission, node-based forwarding, duplicate suppression, and immediate tolerance of failures. It shows how the ring keeps operating continuously, how traffic from non-HSR devices is integrated through a RedBox, and how every device cooperates to maintain seamless redundancy without depending on traditional switch-level recovery mechanisms.

Conclusion

High-Availability Seamless Redundancy provides a robust and deterministic communication method for IEC 61850 digital substations. By sending duplicate frames in opposite directions and allowing each device to forward traffic, HSR guarantees continuous communication even when failures occur. Its predictable forwarding delays, built-in duplicate suppression, and zero-time recovery make it ideal for demanding applications such as Sampled Values, GOOSE messaging, and real-time automation.

When designed correctly, High-Availability Seamless Redundancy becomes a stable foundation for the process bus, ensuring that protection systems always receive the information they need. With proper engineering principles, it delivers reliability, simplicity, and continuous operation, supporting the transition toward fully digital and future-ready substations.